[Are they really spoilers if you’re talking about history?]

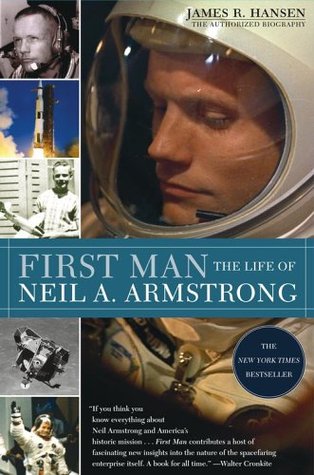

Like many people, I finally picked up my family’s copy of the Neil Armstrong biography in anticipation of the movie adaptation. In the end, I never got around to seeing the film, which is just as well because the book to me a long time to finish.

James Hansen’s account of Neil Armstrong’s life is by no means light reading. I do not say that as criticism. First Man is the sort detailed, technical account I’d been seeking in my recent nonfiction reading and found sorely lacking. Many biographers, historians, and science writers shy away from providing too much information about their subject-matter, but not Hansen. He provides just enough to give a satisfying, comprehensive description of the first man to walk on the Moon.

The story begins long before spaceflight was even a concept. Hansen relates Armstrong’s genealogy from the time his ancestors arrived in America and a detailed account of the future-astronaut’s childhood. While it’s clear that Neil was a precocious and intelligent youth, many apocryphal stories have strung up about his ambitions and destiny to be a space traveler. Hansen does his best to refute these, citing many interviews with Armstrong, his family, and compatriots. Ultimately, there’s no strong case that young Armstrong wanted to be an astronaut. His first love was aviation, and he considered his aeronautical engineering work some of his most important contributions to history.

Armstrong received his pilot’s license at 16 and enrolled at Purdue University with the aid of the Navy. Halfway through his college career, he was called up to serve. He finished Naval aviator training in August of 1950 and was assigned to one of the first all-jet fighter squadrons aboard the USS Essex. He flew in Korea from 1951 to 1952, losing several aircraft and several friends before returning to the States and completing his degree.

Upon graduation, he went to work for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. Armstrong was an engineering test pilot at Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory. He stayed at Lewis less than a year before successfully applying for a transfer to the NACA research facility at Edward’s Air Force Base.1 He moved out there in 1955, shortly thereafter marrying his college sweetheart, Janet Shearon.

At Edwards, Armstrong continued his career as a test pilot, flying all number of aircraft, but most notably the X-15. The rocket-powered airplane was capable of exceeding some formal definitions of space, but Armstrong never flew it that high. He did, however, have a famous flight where he overshot the landing zone by hundreds of kilometers after losing control above the sensible atmosphere. He ended up over the Los Angeles area and had to glide all the way back to Edwards, setting an X-15 time-of-flight and ground-track endurance record when be touched down, barely inside the intended area.

Neil Armstrong with the X-15 after completing his first test flight in the aircraft.

Source: NASA

While Armstrong was technically a member of the earliest astronaut class, he was not formally selected as a civilian astronaut till August of 1962, after the death of his daughter Karen to a rare form of childhood cancer. Many speculate that that loss is what prompted Armstrong to apply to a more advanced position, but he never explicitly confirmed or denied that proposition. In any case, Neil Armstrong became a member of the second NASA astronaut class, training primarily for Gemini missions (but with an eye towards later Apollo flights).

Gemini was more than enough to keep the fledgling Astronaut Corps occupied, with most astronauts serving as part of either an upcoming primary, backup, or support crew at any given time. Adding to the stress, the Armstrongs suffered a house fire not long after moving to Houston, destroying many of their possessions and forcing them to build a second time. Even for families which didn’t experience disaster, having an astronaut in the household was extremely straining. In the end, over half the Apollo astronauts either divorced or separated at some point after their flights. Apollo 17 commander Gene Cernan speaks quite candidly about the matter and how such an absorbing career was a recipe for broken relationships (his own included).

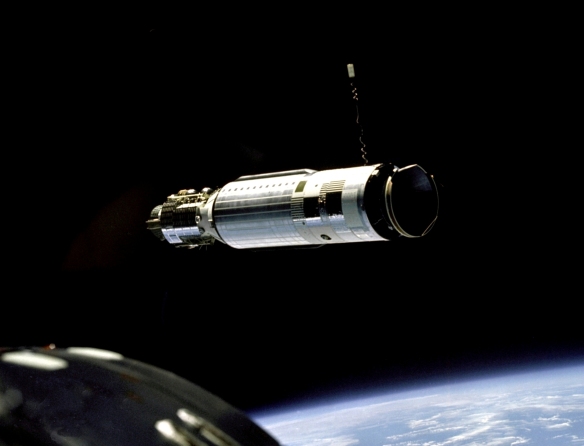

Long before his divorce, however, came Neil’s first spaceflight, Gemini VIII. With NASA’s aggressive schedule and expansion of the Astronaut Corps, first-time space travelers were often given mission commands. Armstrong was one such example. He and Dave Scott were to rendezvous and dock with a satellite already on orbit. Scott would then perform an EVA. The crew would perform several additional dockings and experiments over the course of three days in space.

The Agena Target Vehicle seen from Gemini VIII during approach.

Source: NASA

Ultimately, this did not come to pass. After docking with the target vehicle, a short-circuit in the Gemini capsule locked one of the thrusters in the firing position, rolling the docked spacecraft despite commands to stop. Though they finally managed to regain control of the capsule after undocking, their limited remaining fuel forced them to abort the mission relatively early on.

Armstrong was not assigned to a prime crew for another Gemini flight, though serving as a backup crew and capsule communicator still ate up his time. A few months after their flight, Neil and Janet (along with Dick Gordon and his wife, Barbara) were assigned to a Latin American good-will tour. Neil talent for language and efforts to learn about the local culture charmed crowds and impressed George Low, the senior NASA representative on the tour. Low was, at that time, serving as Deputy Director of the Manned Spacecraft Center—a position giving him significant influence over flight assignments. Hansen speculates that Armstrong’s public speaking performance in Latin America may have been a factor in Neil’s assignment to command the first lunar landing attempt, but the Apollo flight assignments were still a long way away.

The Apollo 1 fire completely rewrote that chapter of history.

On the afternoon of 27 January 1967, a flash fire roared through the Apollo 1 command module, killing all three astronauts onboard. It was a dress rehearsal countdown; technicians were standing by, but the complex design of the capsule hatch prevented them from opening the spacecraft until it was far too late.

NASA took several months to investigate the cause of the fire, and for the prime contractor to implement the necessary changes to avert future disaster. Though it never flew, Apollo 1 was listed as an official flight, with unmanned tests of the Saturn boosters and payloads becoming Apollos 2 through 6. Once the formal accident investigation report was published in April of 1967, Deke Slayton handed out new flight assignments, starting from Apollo 7.

Armstrong was slated as the backup commander of Apollo 9, with Buzz Aldrin and Jim Lovell as his crew. Using the regular crew rotation scheme, they would become the prime crew two flights later. Under NASA’s planned progression at that time, Apollo 11 would have been the in-space dress rehearsal for the lunar surface landing. Contingent on the success of the preceding missions, Apollo 12 would make the actual landing.2

Over the coming months, NASA’s schedule developed. Each subsequent Apollo mission proved a success, and soon it became clear that Apollo 11 would be the lunar landing attempt. By this time, Michael Collins had been moved into the the Command Module Pilot role, to remain in orbit with the other two attempted the surface landing.3

For a time, who would first set foot on the surface was a serious question. Armstrong considered the Lunar Module touchdown far more significant than the surface EVA, but history has clearly disagreed. Many in the Astronaut Office and NASA more generally perceived Aldrin as actively campaigning to be first out, though others disagree with that assessment. There’s some evidence that NASA made a political decision to have the commander out first during Apollo, when pilots performed EVAs during the Gemini missions. In the end, though, there were good technical reasons for supporting the decision, which held throughout the Apollo program.

Hansen gives a vivid account of the lead-up to Apollo 11, including the training Armstrong and Aldrin underwent to prepare for the descent. NASA originally tried to train astronauts using helicopters, but eventually chose to commission specialized vehicles to prepare them for flying “wingless on Luna.” Neil famously destroyed a Lunar Landing Research Vehicle when a pressurant leak led to loss of control authority, nonchalantly returning to the Astronaut Office and getting back to work within an hour of ejecting.

Armstrong ejects to safety from the LLRV on 6 May 1968.

Source: NASA

I won’t attempt to summarize the flight of Apollo 11, just read the book. First Man gives a real blow-by-blow of Armstrong’s space flights, quoting the mission transcripts and post-return testimony at length. The chapters are, I think, accessible to laypersons, but provide the sort of detail that aerospace engineers will appreciate.

(I wouldn’t have said no to extensive tables and figures, of course.)

Returning from Luna was its own ordeal. The flight back was relatively routine, but the reception was something else. They spent three weeks in a quarantine facility, where there were confined against the off chance that malicious microbes were hiding in the lunar regolith. The astronauts and quarantine staff were released after a NASA physician deemed them non-infectious.

The astronauts and their families visited New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles in a day. A parade welcomed them back to Houston. After short vacations, the astronauts visited their home towns and Washington, D.C., before embarking on a world-wide good-will tour. Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins addressed millions of people and told them about the mission. The astronaut’s role as a public intellectual began to emerge—nothing else was possible. Many around the country and world were upset over various issues (such as Vietnam, pollution, and poverty) and as symbols of the United States Government, the astronauts took a lot of heat.

Oddly enough, that animosity did not extend to the Soviet space program. Armstrong was invited to visit the Premier in Moscow and the cosmonauts in Star City, finding a warm welcome. But perhaps they more than anybody understood what a technical feat landing human beings on the Moon really was.

Valentina Tereshkova presents a badge to Neil Armstrong during his visit to Star City. Tereshkova’s husband, Andriyan Nikolayev, launched aboard Soyuz 9 that same day.

The crew went their separate ways after the good-will tours wound down. Armstrong, realizing he would be denied the opportunity for further flights on political grounds, accepted a position as Deputy Associate Administrator for Aeronautics at NASA.4 This was a return to his original love, aviation, but was a temporary situation. He left NASA after a little over a year in that position. He completed the master’s degree he had been pursuing when he joined the Astronaut Corps (with an entirely different thesis topic, discussing his recent mission) and accepted a position teaching aerospace engineering at the University of Cincinnati. This, too, was short lived, and he left after 1979.

Public life was stressful for Armstrong and his family. In Cincinnati, he was initially hounded by reporters and frequently received personal fanmail at his university mailbox. The transition from local to state university was complex and led many professors to resign or retire, Armstrong included.

He accepted positions on the board of directors for a number of firms and organizations, which provided an adequate income. Contrary to public perception, Armstrong never considered himself particularly withdrawn—simply that public interest for his presence at events and so-on far, far outstripped his ability to attend.

Armstrong provided his voice and reputation to various engineering organizations, including the Challenger disaster investigation. His focus was always on quality technical work, rather than making a splash. Perhaps that dedication to excellence over fame contributed to his reputation as a recluse.

The pressures of being an astronaut and public figure eventually led to his divorce. Janet felt unsatisfied with their marriage and initiated divorce proceedings in 1989. Neil was unhappy with the change and was depressed for a time, simultaneously dealing with his parents’ deaths. He was introduced to widow Carol Held Knight during a social function by mutual friends, and remarried in 1994.

All told, I found Hansen’s biography an enlightening illustration of Neil Armstrong’s life from boyhood to dealing with the media in his retirement. It paints a clearer picture of Armstrong as an engineer, an astronaut, a professor, and a celebrity. It is a long and dense book, but precisely because of that, I recommend it as a detailed look at America’s early space program, culminating in the first manned lunar landing.

It is also a cross-section of the United States and world during a century of upset. From a small-town Depression upbringing to arguably the most famous person in the world is quite a range of experience. Astute readers will note the complex changing world—a world which Armstrong (and millions of others) helped change.

Armstrong resisted the claim that his landing was somehow significant; if not him, then one of the other astronauts.5 Apollo 11 was the ultimate test flight, and Neil Armstrong was a dedicated research pilot and flight test engineer. The Moon landing was inherently significant—the landees, less so.

Still, as one of the Apollo 11 astronauts, Neil Armstrong’s name will be embedded in the history books as long as our civilization survives. Hansen has done the future an amazing service writing a dedicated book about Neil Armstrong, one well-worth enjoying in the present.

1Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory, located in Cleveland, is now known at Glenn Research Center. NASA’s Edwards facility went through a number of functional names before becoming Dryden Flight Research Center in 1976. In 2014, it was renamed again to Armstrong Flight Research Center.

2Apollo 11 moved up because NASA decided it could afford to skip the planned E Mission in high Earth orbit. Apollo 7 and 9 remained tests in low Earth orbit, with Apollo 8 and 10 making the full trip to Luna. Originally the flight sequence called for Earth orbital tests to be conducted first, but delays with the Lunar Module led to the decision to conduct the lunar orbital mission first.

3This is sometimes lamented in popular culture, but Collins would have probably been given the command for a later landing attempt under the regular crew rotation. Collins did not remain in the Astronaut Corps that long, opting to retire before flying Apollo 11.

4Yuri Gagarin, Valentina Tereshkova, and John Glenn were grounded for similar reasons. This protection did not prove to be adequate: Gagarin died in an airplane crash in 1967. The Soviet leadership then grounded their second cosmonaut, Gherman Titov, who remains to date the youngest person in space.

Glenn holds the record for oldest person in space, returning to orbit as a septuagenarian aboard the space shuttle. Alan Shepard, the first American in space, flew again after overcoming a medical disqualification, commanding the Apollo 14 lunar landing.

5Deke Slayton, Chief of the Astronaut Office, has said that, if the Apollo 1 fire had not occurred, he would have given Gus Grissom the first lunar landing command. There are also reports that Slayton later offered the command to Frank Borman, who turned it down.